Bussiness

Trump’s message of American decline resonates in Michigan

BBC

BBCKamala Harris may have rattled Donald Trump on the debate stage, but the former president’s promise to save a nation in decline resonates with undecided voters in this part of a key battleground state.

It took Paul Simon four days to hitchhike from Saginaw, or so he sang in America, his iconic soundscape ballad of the 1960s with its lost souls on the highways of a country in flux.

Back then, this city’s long, slow decline had already begun, as Michigan’s once mighty car factories pulled down the shutters, buffeted by the winds of foreign competition.

Today, the angst and loneliness of Simon and Art Garfunkel’s song are magnified many times over.

I found 57-year-old Rachel Oviedo sitting on her porch, staring out at abandoned furniture in the street and beyond, the shell of a plant that once made car parts for Chevrolets and Buicks, but finally closed its doors in 2014.

“We sit here all day long,” she told me. “We see homeless people come in and out of there, they need to tear it down and make something out of it.”

“A grocery store,” she suggested. “Because we ain’t got no grocery stores round here.”

I first met her the day before Tuesday night’s debate in Philadelphia, when she told me she was still unsure of how she was going to vote.

Donald Trump, she said, felt like a known quantity and like “a man of his word”, while Kamala Harris looked promising but still somewhat unknown.

“I like her,” she said, “but we don’t know what she’s going to do.”

Most US states lean either so strongly Democratic or so strongly Republican that the result is a foregone conclusion.

And if Michigan is one of the few swing states, then Saginaw is one of the few places in it where the vote could genuinely go either way.

When they come to cast their ballots, it will be undecided voters like Rachel, in places like this, who’ll quite literally have the future of America in their hands.

Chuck Brenner, a retired Saginaw cop, is another one.

The 49-year-old, who still works part time in probation and runs his own real estate company, says he’s seen up close the problems here.

“Almost everybody’s dad worked in the car industry,” he told me.

“Back then, everybody had money and jobs were readily available. You’ve seen the change, people are struggling because people are growing up poor and then drugs and all that.”

Trump’s message of American decline resonates with Chuck.

“Absolutely,” he told me. “Because you can see it.”

But although he voted for Mr Trump in 2016, he went for Joe Biden in 2020.

“There was a lot of drama with Trump,“ he added. “And the legal issues. I kind of got sick of that.”

This time round, he’d only make up his mind, he insisted, once he’d watched the debate and heard what both candidates had to say.

Saginaw, like the wider state of Michigan, was once solid Democrat country – its political inclinations revealed in the list of candidates it has backed down the decades: Bill Clinton, Al Gore, John Kerry, Barack Obama and Joe Biden.

That 2016 vote, when Saginaw went – like Mr Brenner – for Trump, marked a shift.

You don’t have to spend long here to realise just how remarkable a shift that was.

Jeremy Zehnder runs a truck-polishing company, doing the kind of work Democrats used to be able to depend on for support.

Surrounded by the giant, gleaming trucks and trailers, the lifeblood of the American economy’s distribution networks, he tells me it’s not debate performances, but the cost of living that will determine how he votes.

And a majority of voters tell pollsters they trust Trump more on the economy.

“With the truckers, every one of those that we know of are leaning towards the right,” he told me.

“What, every one?” I ask.

“I don’t know of one that isn’t,” he replied. “I mean we do hundreds of trucks every year. And they all want to talk about it, everybody talks about it.”

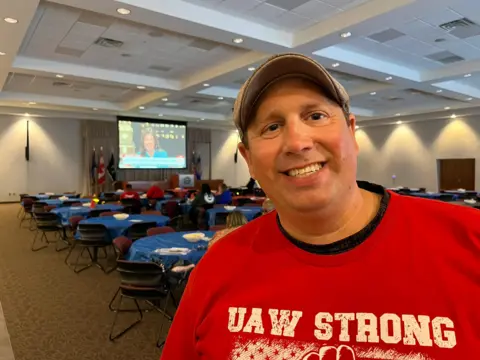

At a United Auto Workers Union event where members watched the debate, I met one of the union organisers, Joe Losier.

The UAW has pledged its support to Kamala Harris and much of the crowd in the room whooped and clapped with every put-down she threw Trump’s way.

But dig a bit deeper and the fault lines of America’s political upheaval can be found here, too.

“My dad and all my uncles on both sides of my family, who are all UAW people, have become Republicans,” Mr Losier told me, unable to hide the incredulity in his own voice.

“These are second generation immigrants who came over here, started working in the auto industry back in World War One and it blows my mind that a lot of my family are tradesmen who are supporting Donald Trump.”

He’s even unsure which way his two adult sons are going to vote.

Dinner times are “horrible”, he said.

With workers fearing further shift cuts and job losses, the union finds itself increasingly out of step with its members.

There’s deep support here for Donald Trump’s promise of tough tariffs on imports, and disagreement with Kamala Harris’s argument in the debate that the policy would simply drive up prices.

After the debate, I called Chuck Brenner to see what he’d made of it. He had some good news for Democrats.

“I do believe Kamala was the shining star,” he told me. “And the bottom line is she’s won my vote. I was impressed by what she had to say, her delivery.”

“With Trump,” he went on, “it was kind of what I expected. There were no surprises there. It’s kind of like the same. The same.”

Rachel Oviedo was still undecided, she told me, but now leaning more towards Trump.

“I think he’ll do more for us up here,” she said.

“You know, he did things he shouldn’t have done”, she added. “But you gotta forgive people.”

And Jeremy Zehnder, the truck polisher, admitted to being slightly surprised by Harris’s performance.

“She did much better than I thought she would,” he told me. “I think she won it.”

But he’s sticking with Trump. It’s about policy, he said. Taxes, the border and the cost of living.

On the streets of Saginaw, Kathleen Skelcy was knocking on doors, busy canvassing for Harris.

She told me she finds it a struggle to see any rationale behind the political motivations of her opponents.

“That’s what’s scary, trying to understand these people and their thinking,” she said.

“I just think they’re not educated, or they fell asleep in school or something.”

It’s easy to see this as patronising, another sign that some Democrats chalk Trump’s appeal as merely delusional.

It’s clear, however, that trust and understanding can be in short supply on both sides.

As we’re talking, a Trump supporter, aggressive and threatening, emerges shouting from his home, following Kathleen up the street.

“Harris is a clown,” he yells, adding a few profanities for good measure.

And on the doorsteps, one Democratic supporter declines the offer of a Harris sign for their front yard, scared, they say, of inviting similar abuse.

In a few weeks, Saginaw will go the polls.

Before then, it’s almost certain that many more journalists will pass through this key bellwether district, all of them looking for America.

It’s here alright, in all its striving and struggling, and in a story today being lived out in stark political division.

A debate needs middle ground.

And there’s very little of that left.

North America correspondent Anthony Zurcher makes sense of the race for the White House in his weekly US Election Unspun newsletter. Readers in the UK can sign up here. Those outside the UK can sign up here.