Jobs

Key facts about U.S. poll workers

Millions of Americans are heading to the polls, entrusting their ballots with local poll workers. But what exactly these poll workers do – and the requirements they must meet to assume this role – varies widely by state and county.

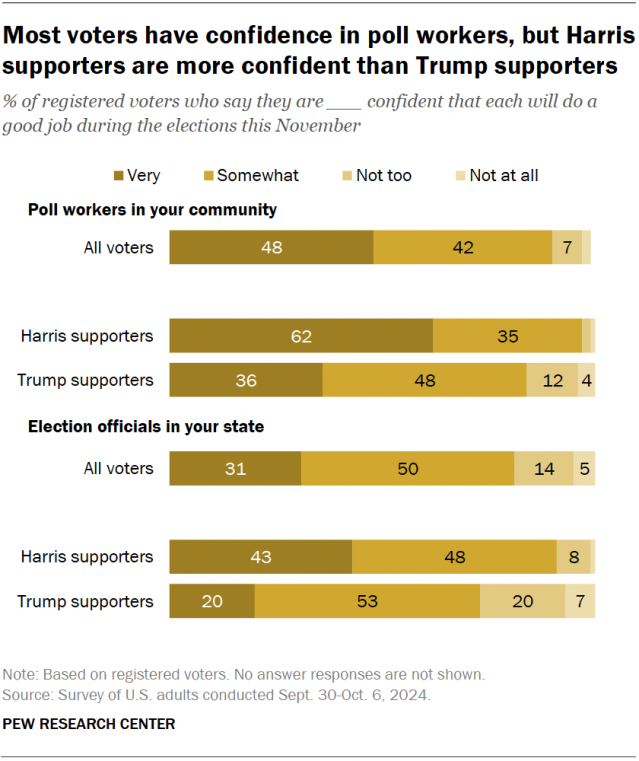

Overall, U.S. registered voters tend to trust poll workers. Nine-in-ten registered voters say in a new Pew Research Center survey that they are at least somewhat confident that poll workers in their community will do a good job during this year’s elections. In fact, voters are more likely to express confidence in poll workers than in state officials who run elections (90% vs. 81%).

Large majorities of voters who back Vice President Kamala Harris and those who back former President Donald Trump express at least some confidence in poll workers. But Harris supporters are much more likely than Trump supporters to say they are very confident (62% vs. 36%). Harris supporters are also more likely than Trump supporters to be very confident in state election officials (43% vs. 20%).

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to provide key facts about U.S. poll workers ahead of the 2024 presidential election.

Center survey data on registered voters’ trust in local poll workers comes from a survey of 5,110 U.S. adults, including 4,025 registered voters, conducted Sept. 30 to Oct. 6, 2024. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Here are the questions used for this report, the topline and the survey methodology.

Data on U.S. poll workers for the 2020 and 2022 general elections comes from the biennial Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS) conducted by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC). The EAC is an independent, bipartisan commission that provides election officials with information to “improve the administration of elections and help Americans participate in the voting process.” The latest EAVS was fielded between November 2022 and March 2023; refer to its methodology for more information. Calculations in this analysis exclude U.S. territories.

For information on state laws and requirements for poll workers, we consulted the EAC’s 2023 “State-by-State Compendium of Election Worker Laws and Statutes,” the National Conference of State Legislatures’ 2020 “Election Poll Workers” report, news reports, and individual states’ laws and Election Commission websites.

Here are key facts about poll workers in the United States, including:

What do U.S. election workers do?

There are three types of election staff, but poll workers account for the bulk of them:

- Poll workers are temporarily recruited to perform various duties on Election Day and the lead-up to it. Their duties can include setting up voting equipment, greeting or checking in voters, verifying voter IDs and registration, serving as language interpreters, counting ballots, and more. Poll workers hold different titles – such as election clerk, election judge, inspector, booth worker, warden or commissioner – depending on the state or county.

- Election officials are elected, appointed or otherwise hired to carry out specialized activities like recruiting and training poll workers and maintaining voter rolls. They work year-round, and many have additional duties beyond election administration.

- Poll watchers are not typically government employees. They’re generally appointed by political parties to observe the opening of the polls and ballot counting. They may be party or candidate representatives, members of nonpartisan groups, academics, or part of special interest groups with stakes in local ballot measures.

How many poll workers usually help in general elections?

Looking at polling sites with available data, roughly 644,000 poll workers assisted with in-person and/or early voting in the 2022 general election. This includes data from 45 states and the District of Columbia collected by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), a study conducted every two years to examine how states administer federal elections.

Data was unavailable for New Hampshire, Vermont and Wisconsin, as well as for the country’s two fully vote-by-mail states: Oregon and Washington. (Hawaii, which is included in these figures, primarily conducts voting by mail but still has in-person voting at staffed polling sites.)

By comparison, about 774,000 poll workers helped in the 2020 general election, according to EAVS data from polling sites that provided this information in 44 states and D.C. (This total excludes data from the same states as in the 2022 survey, as well as Pennsylvania.)

Related: Republicans, Democrats continue to differ sharply on voting access

Which states have the most poll workers per polling site?

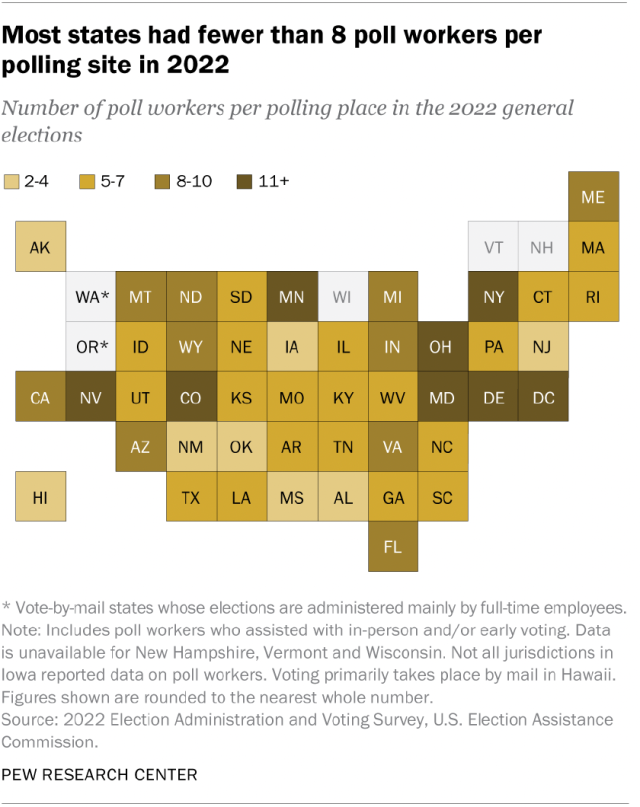

D.C. topped the list with 23 poll workers per site in the 2022 general election. Colorado (15 per polling place), Nevada (14), New York, Maryland and Minnesota (12 each) rounded out the top six.

In 2022, 28 of the 45 states and D.C. with available data had fewer than eight poll workers per site. (This total includes Iowa, but some jurisdictions there did not report the number of poll workers they had that year.)

Are poll workers paid?

The amount of compensation poll workers can receive varies widely by state and county. Minimum requirements are typically set on the state level – with some using the federal or state minimum wage as a basis – but local jurisdictions sometimes opt to pay their workers more.

While election clerks in Delaware are entitled to a $300 stipend, for example, many poll workers in Alaska are eligible to make $20 an hour. Colorado law requires election judges to be paid at least $5 per day.

Poll workers can also often be reimbursed for travel expenses or paid for completing trainings.

Several states, including New Jersey, Oklahoma and Alabama, have raised their minimum compensation requirements for poll workers in the past few years to incentivize more recruits. Most recently, South Carolina’s Election Commission requested a budget increase to fund a $40 daily raise for the Palmetto State’s poll workers.

What criteria must poll workers meet?

Across D.C. and the 48 states that have in-person voting, requirements vary widely – even for poll workers serving different roles in the same precinct. But some similarities emerge:

- All states have minimum age requirements, most often set at 18, but many allow students as young as 16 to serve under certain limitations.

- Forty-one states, plus D.C., explicitly require volunteers to be registered voters. In Minnesota, North Dakota and Wisconsin, they must at least be eligible to vote.

- Every state but Hawaii – where voting primarily takes place by mail – has explicit residency requirements. States often mandate that poll workers reside in the county or precinct of the polling place, but many allow some flexibility for outsiders if there are volunteer shortages.

- Poll workers are explicitly required to have a party affiliation in at least nine states. In about half of the 48 states that offer in-person voting, it’s “considered,” “preferred” or “generally” required unless there aren’t enough volunteers who affiliate with a major party. Some states – such as New York, for example – require poll workers or election officials to equally represent the two major political parties, depending on the worker’s position.

- The vast majority of states require poll workers to undergo trainings, which are commonly held at the local level.

- At least 37 states, plus D.C., require at least some poll workers in certain positions to swear an oath.

Arkansas poll worker oath

“We, the undersigned, do swear that we will perform the duties of poll workers of this election according to law and to the best of our abilities, and that we will studiously endeavor to prevent fraud, deceit, and abuse in conducting the same, and we will not disclose how any voter shall have voted, unless required to do so as a witness in a judicial proceeding or a proceeding to contest an election.”

Elected officials, candidates and their families, political action committee members, and people with felony records are typically barred from serving as poll workers. People who’ve bet on elections or committed certain crimes are also sometimes prohibited.

Some states also set additional “good reputation” requirements. For example, poll workers in Georgia must be “be judicious, intelligent, and upright citizens” while those in New Jersey must be “of good repute and character.” Virginia simply requires that they are “competent citizens.”

What are common recruitment challenges?

While Nebraska law allows counties to draft people – jury duty-style – to meet staffing needs, most U.S. poll workers are volunteers. With more than 94,000 polling sites to staff nationwide, recruiting enough people can be a challenge.

Specific hurdles, such as a lack of public awareness about the job or disinterest in the long hours and relatively low pay, have been widely cited by news outlets and research organizations. Public health was also a worrisome issue for poll workers – the majority of whom are older than 60 – during the 2020 election, which coincided with the coronavirus pandemic.

Personal safety concerns among poll workers also intensified that year and continue to linger. The Department of Justice recently warned that harassment against poll workers may persist – and potentially worsen with the use of AI – in the 2024 election. Many states have responded to these concerns, with 18 enacting legal protections for election officials and poll workers since 2020, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Creative recruitment methods have subsequently cropped up in several states, such as enlisting military veterans for the job in the hopes of increasing public trust in poll workers. Election officials in places that allow younger workers have also recently pushed to mobilize college and high school students to volunteer at polling sites for the 2024 election.

| State | Must be registered voter | Residency requirement | Party affiliation explicitly required |

| Alabama | Yes | County, but precinct is sometimes prioritized | Generally |

| Alaska | Yes | Precinct; if insufficient staffing, can recruit district residents, then state residents | Generally |

| Arizona | Yes | Precinct, then county or other precincts | Required for some positions |

| Arkansas | Yes | Precinct, then county | Generally |

| California | Yes | State | |

| Colorado | Yes | State | Generally |

| Connecticut | Yes | Generally town or district | Generally |

| Delaware | State | ||

| District of Columbia | Yes | D.C. resident (except D.C. govt. employees) | |

| Florida | Yes | County | |

| Georgia | Generally county for county residents or employees | ||

| Hawaii | |||

| Idaho | No legal requirement, but precinct is the norm | Preferred | |

| Illinois | Yes | Generally precinct, but county for some positions | Required |

| Indiana | Yes | County | |

| Iowa | Yes | Precinct preferred, then county | Generally |

| Kansas | Yes | Area of polling place or county | Required |

| Kentucky | Yes | Precinct, then county | Generally |

| Louisiana | Yes | Any precinct in ward; if insufficient staffing, can recruit residents from parish | Required |

| Maine | Yes | Municipality or county | Required for clerks |

| Maryland | Yes | County, then state | Preferred |

| Massachusetts | Yes | Commonwealth | Preferred, but a limited number of nonaffiliated workers are allowed |

| Michigan | Yes | State | Required |

| Minnesota | * | Precinct is the informal norm, but state is the requirement | Required |

| Mississippi | Yes | County | Certain positions may only be filled by members of one political party if recruits with other party affiliations cannot be found |

| Missouri | Yes | Jurisdiction, unless insufficient number found | Generally preferred; Missouri election judges are required to provide their party affiliation. |

| Montana | Yes | Precinct, then county | Required |

| Nebraska | Yes | County residency required for places with election commissioners; for places without election commissioners, precinct residency is preferred, but county is allowed | Generally |

| Nevada | Yes | County | Required |

| New Hampshire | Yes | Voting district (polling place) | Required for some positions |

| New Jersey | Yes | County | Generally |

| New Mexico | Yes | Precinct, then county | Considered for election judges |

| New York | Yes | County (or city for NYC residents) | Poll workers must be equally divided between the major political parties |

| North Carolina | Yes | Generally precinct | |

| North Dakota | * | Precinct, then legislative district, then county | Required for some positions |

| Ohio | Yes | County | No more than half of poll workers should be from the same political party |

| Oklahoma | Yes | County | Required |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Election district | |

| Rhode Island | Yes | City, town, senatorial or representative district, or voting district | Considered |

| South Carolina | Yes | County or adjoining county | |

| South Dakota | Yes | Generally precinct | Required |

| Tennessee | Yes | State house legislative district or county | Preferred |

| Texas | Yes* | Generally precinct or county | Generally |

| Utah | Yes | County, municipality or district | Generally for election judges |

| Vermont | Yes | Municipality | Considered |

| Virginia | Yes* | Precinct, then commonwealth | Generally |

| West Virginia | Yes | Generally county or municipality | Generally |

| Wisconsin | * | County | Generally |

| Wyoming | Yes | County | Generally |

Note: Washington and Oregon are vote-by-mail states without traditional poll workers; they are not shown. Voting primarily takes place by mail in Hawaii. Requirements may vary by poll workers’ positions, and local jurisdictions may set their own additional requirements. Voting registration requirements may differ for student workers under 18 in states that allow them. States’ residency requirements often allow those from elsewhere in the state (i.e., outside of the required precinct, county, etc.) to serve if not enough recruits can be found.

Source: U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s 2023 “State-by-State Compendium of Election Worker Laws and Statutes”; National Conference of State Legislatures’ 2022 “Election Poll Workers” report; news reports; and individual states’ laws and Election Commission websites.

Note: This is an update of an analysis originally published on July 25, 2024. The update includes new survey data about public perceptions of poll workers. All other information is unchanged. Here are the questions used for this analysis, the topline and the survey methodology.