World

Can Puerto Ricans vote in the presidential election? What role do US territories play in elections?

With Puerto Rico in the headlines, we asked Amílcar Barreto, professor of cultures, societies and global studies, to clarify the role U.S. territories play in elections.

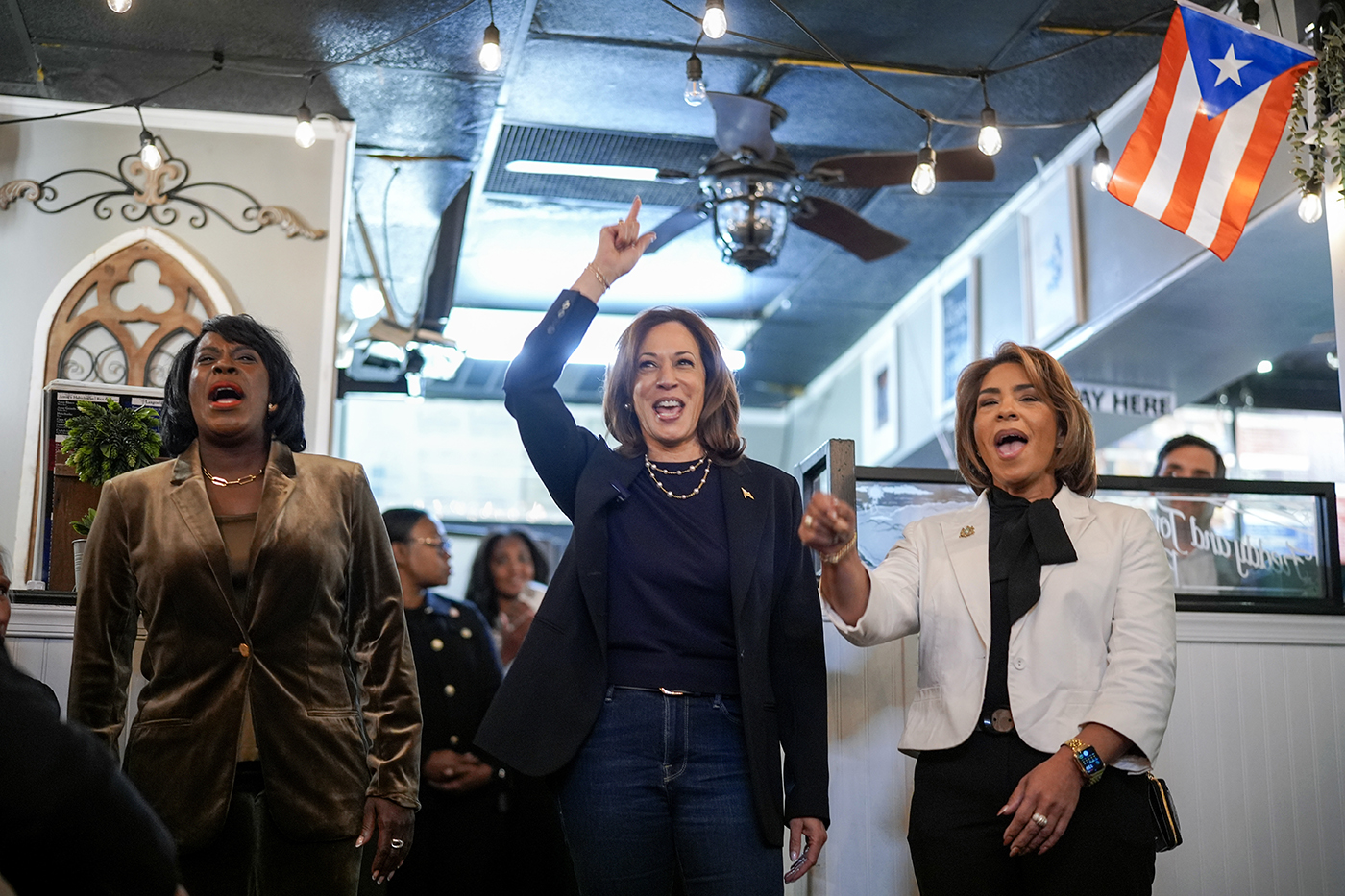

Puerto Rican celebrities are out en masse responding to a comedian’s crude comments about the island territory during former President Donald Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally over the weekend. Then on Sunday, Vice President Kamala Harris unveiled a new policy platform she called the Puerto Rico Opportunity Economy Task Force.

With Puerto Rico in the headlines, we asked Amílcar Barreto, professor of cultures, societies and global studies at Northeastern, and interim director of the university’s International Affairs Program, to clarify the role U.S. territories play in electoral politics. His comments have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Can Puerto Ricans vote in the presidential election?

Puerto Ricans who live on the island can’t vote in federal elections as set forth in the U.S. Constitution. Consequently, they do not have full representation in Congress. This applies to all other U.S. territories, which are limited to sending to the U.S. House “one non-voting territorial delegate,” Barreto says.

But Puerto Ricans residing in the U.S. can vote by absentee ballot, or, alternatively, travel to their respective states to cast their ballot. “So Puerto Ricans who live on the U.S. mainland — and, at this point, almost two-thirds of ethnic Puerto Ricans live on the U.S. mainland, not on the island — can vote,” Barreto says.

But all Puerto Ricans, including islanders and those residing on the U.S. mainland, can participate in the U.S. primary process. Voters in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories are, therefore, granted delegates from the two major parties.

How did we arrive at the status quo?

The Spanish-American War resulted in the U.S. annexation of the Philippines, Hawaii, Guam and Puerto Rico. The question then, at the turn of the 19th century, was whether the people living in the new territories should be considered U.S. citizens.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, these islands “belonged to, but were not a part of” the United States. That was the court’s reading of the situation in the so-called Insular Cases — a series of opinions issued in the aftermath of the war that sought to clarify the legal and political status of the “unincorporated” territories.

“Federal law can establish different rules for the overseas territories,” Barreto says. “It could not, because of the uniformity clause, do that to the U.S. states, however.”

For over a century, Puerto Ricans have grappled with the question of Puerto Rico’s status. And the ideas that have sprung up have ranged from maintaining the status quo, which posits that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens without full rights, to embracing various independence movements, which posit an autonomous, or semi-autonomous, Puerto Rico. Others have advocated for Puerto Rico’s admission into the union as the 51st state.

A nonbinding referendum is scheduled for Nov. 5 in Puerto Rico, occurring alongside the Puerto Rican general election, that will probe residents’ preference for a future form of government. Their choices include sovereignty with free association, statehood and independence.

Far from powerless in U.S. elections, Puerto Ricans make up the second largest voting bloc in the U.S., according to Pew Research Center. As of 2021, there were roughly six million Puerto Ricans residing in the U.S. mainland.

At home, Puerto Rican political system is not that dissimilar from other democracies. As a self-governing territory with a republican form of government, Puerto Rico has a multi-party political system, with three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial.

“Historically, voter participation rates on the island of Puerto Rico were much higher than voter participation rates on the U.S. mainland,” Barreto says.

“For over a half a century, we had a very stable political system. The two biggest parties would collectively get roughly 95% of the vote — one of them was for statehood, one was for the status quo — and that was very stable since the late 1960s,” he says.

Barreto continues: “The last election, the two major parties only got 60-plus percent, so the party system on the island is collapsing. What it will transform into — I don’t know.”