China has banned shipments to the US of several minerals and metals used in semiconductor manufacturing and military applications, in a rapid retaliation by Beijing against new export controls from Washington.

China’s commerce ministry on Tuesday said it would prohibit the export to the US of dual-use items that include gallium, germanium, antimony and superhard materials, and would impose stricter controls related to graphite.

The ministry said Washington was “weaponising trade and technology” in the guise of national security. The retaliation came after the US on Monday imposed another round of sweeping export controls that are designed to make it harder for China to develop artificial intelligence for its military.

“To safeguard national security . . . China has decided to strengthen export controls on dual-use items to the US,” said the ministry, which added that the measures would be effective immediately.

Separately, four major Chinese trade associations that represent the internet, auto, semiconductor and communications industries reacted to the US moves by telling members to reduce purchases of American chips.

“US chip products are no longer safe or reliable, and relevant Chinese industries should be cautious in procuring US chips,” said the China Semiconductor Industry Association.

The embargoed minerals and metals are used in the production of semiconductors and batteries, as well as communications equipment components and military hardware, such as armour-piercing ammunition.

China had already been strengthening export controls in response to tightening chip sanctions from the US and its allies. Existing curbs on shipments of germanium and gallium have led to an almost twofold increase in the minerals’ prices in Europe.

China’s latest shipment ban to the US makes clear President Xi Jinping’s government is willing to target western economic interests to hit back against Washington’s chip restrictions.

“China had previously concluded that holding fire would slow the pace of decoupling, but they have now concluded that holding fire simply invites greater US sanctions and that they need to push back to impose costs,” said Scott Kennedy, a China expert at CSIS, a Washington think-tank.

The US National Security Council said it was “still assessing” the controls but would take steps to mitigate their impact and to deter “coercive actions” from Beijing.

“These new controls only underscore the importance of strengthening our efforts with other countries to de-risk and diversify critical supply chains away from the People’s Republic of China,” the NSC said.

China experts in the US have been waiting to see if Beijing would step up retaliation against American export controls.

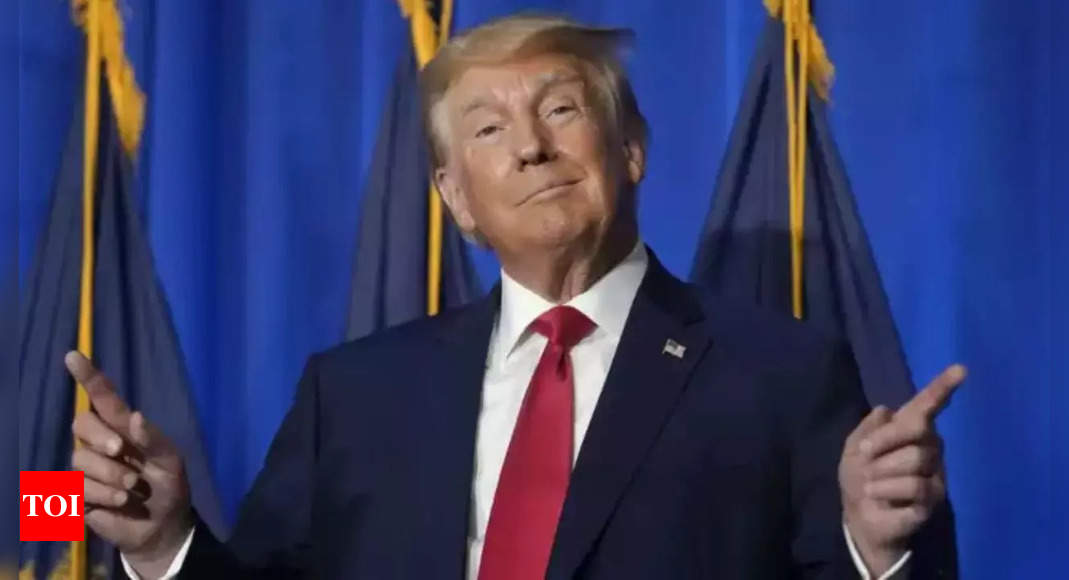

“This is a signal to the incoming Trump administration that China is prepared to respond with retaliatory measures,” said Wendy Cutler, a trade expert at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

Cutler said the immediate impact of the measures was unclear, given that the US had been diversifying its supply chains. “But they could put other products on their export control list which would have a much bigger impact on us.”

Earlier this year, China privately threatened to restrict exports of the critical minerals to Japan if Tokyo signed up to US export controls.

China produces 98 per cent of the world’s supply of gallium and 60 per cent of germanium, according to the US Geological Survey.

The US controls unveiled on Monday included tougher restrictions on the export of critical semiconductor manufacturing tools and a ban on exports to China of advanced high bandwidth memory (HBM) chips, a crucial component in artificial intelligence products.

But Bernstein analysts said the US restrictions were less severe than expected. Japanese chip equipment suppliers were seen as benefiting from the tighter restrictions, with chip stocks leading the Nikkei share average to a three-week high on Tuesday. Tokyo Electron rose 4.3 per cent, and Disco Corp and Lasertec were up 6.1 per cent and 4.3 per cent, respectively.

Washington also added 136 Chinese companies to a US trade blacklist, including major Apple and Samsung supplier Wingtech, which had been working to buy up foreign semiconductor technology.

Since 2018, Wingtech has spent more than $4bn acquiring Dutch semiconductor group Nexperia. It also tried to buy Newport Wafer Fab, Britain’s largest chipmaker, in a deal ultimately blocked by the UK government.

The US blacklisting sent Wingtech’s Shenzhen-listed shares sliding more than 10 per cent over two days and highlighted the delicate balancing act for Chinese companies between growing their international business and supporting Beijing’s policy priorities at home.

Wingtech had previously bought an Apple-related camera module business from another Chinese group after it was hit with sanctions in 2020.

“Western companies no longer buy from us,” said a manager at one blacklisted Chinese firm. “For two years, we basically stopped growing as we replaced foreign components.”

Charlie Chai, of 86Research, said Wingtech could be split up if necessary to retain foreign business. He noted that the latest US controls closed loopholes making it harder for Chinese chip companies to buy foreign equipment.

“It has turned into a classic game of cat and mouse, but the room for manoeuvring is fast shrinking for Chinese firms,” he said.

Wingtech did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Nexperia said the US controls did not apply to it or its subsidiaries.

Reporting by Ryan McMorrow and Eleanor Olcott in Beijing, Christian Davies and Song Jung-a in Seoul, Harry Dempsey in Tokyo, Andy Bounds in Belgium and Demetri Sevastopulo in Washington