Tech

Crypto Asset Investigations: Key Considerations And Pitfalls – Fin Tech – United States

Crypto assets are some of the most rapidly

evolving and increasingly adopted assets in the world.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) is emerging as a blockchain-based

alternative to traditional banking and financial services and has

seen dramatic growth in conjunction with the growth and development

of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology. The associated

regulation and guidance for investigation and enforcement is

constantly evolving given the early-stage nature of this

industry.

The crypto and DeFi industry has seen a growing number of

regulatory enforcement actions as developers and founders push the

boundaries of these fintech applications into areas of our existing

financial regulations that were established well before the concept

of crypto assets was contemplated. In the United States, the number

of Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement actions

related to crypto assets has steadily increased over the last

decade, from a total of 11 between 2012 and 2017 to 128 between

2018 and 2023 (Figure 1).

1

Figure 1: Growth of Digital Asset

Enforcement Actions by the SEC

Source: SEC.gov

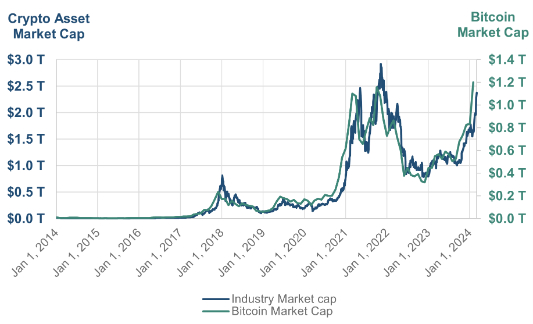

The rise in SEC enforcement actions related to crypto assets has

coincided with significant growth in the total market cap of the

crypto asset industry, which has seen a precipitous rise since

2017. Bitcoin represents the largest share of the overall crypto

asset industry market cap, currently representing approximately

one-half of the total market cap for all crypto assets.

(Figure 2).

Figure 2: Market Capitalization of the

Crypto Asset Industry and Bitcoin

Source: CoinMarketCap.com

The SEC’s first noticeable increase in crypto asset

enforcement actions was in 2018, which followed an all-time high in

the price of Bitcoin and in the industry market cap in December

2017. Similarly, enforcement actions increased in 2021 when the

overall industry market cap and Bitcoin again reached all-time

highs. Given this trend, it seems likely that the SEC and other

regulators and enforcement agencies will continue to increase their

focus on the crypto asset industry.

With the rise of crypto asset enforcement actions and other

related litigation, investigators must familiarize themselves with

the nuances and mechanics in the crypto asset industry,

particularly on the differences to investigations solely involving

traditional financial assets. Below, we will outline some of the

key considerations and major pitfalls that investigators may

encounter on investigations involving crypto assets.

The Basics

It is critical that investigators understand the type of crypto

assets that they are working with and how users will transact with

those assets. A wide variety of crypto assets exist with many

different transaction types, and understanding the nuances between

these assets and transactions is necessary in properly analyzing

the activity and tracing the flow of funds through blockchains and

off-chain entities.

While each crypto asset is unique in terms of its functionality,

supply and distribution characteristics, each crypto asset can be

generally categorized as either a native asset to a specific

blockchain (or a cryptocurrency

coin) or an asset that is built on top of

and operable with an existing blockchain (or a crypto

asset token).

Cryptocurrency coins are necessary to transact with or interact

with the blockchain that the coins are native to and are critical

to the operation of independent blockchains (e.g., Ether

is the native coin of the Ethereum blockchain). Each transaction on

a blockchain requires fees to be paid in the native asset and these

assets are critical to the security and consensus mechanism for

that blockchain, including rewarding blockchain participants for

validating transactions executed on each respective blockchain.

Conversely, crypto asset tokens are digital assets built on top

of and supported by a blockchain but are not native to a

blockchain. The characteristics of these tokens can vary widely,

however, they can be further classified as

fungible tokens or

non-fungible tokens (NFTs). A fungible

token shares the same rights and characteristics as all the other

tokens created by that token’s smart contract. Each fungible

token holds the same value and is interchangeable with every other

identical fungible token issued by the same smart contract. A

non-fungible token is one that is distinct from all other tokens

and does not have the same rights or characteristics of other

non-fungible tokens created by that token’s smart contract.

Wallet and Address Identification

One of the most critical aspects of a cryptocurrency

investigation is the identification of specific addresses and

wallets to analyze. Blockchains and cryptocurrencies inherently

provide a level of privacy and confidentiality as a feature of the

system known as pseudonymity, meaning that users interact with the

blockchain via a public cryptographic address as opposed to using

their full identity. Despite this privacy feature afforded to

users, because blockchains are immutable public ledgers, the

transactional and balance data of each address can always be

accessed and analyzed by investigators experienced in blockchain

forensics, and this data can be used to determine the ownership of

crypto asset addresses.

There are several methods to determine the identity of the

user(s) of a crypto asset address and/or wallet. In some cases,

individuals or entities may publicly identify their own public

addresses on social media platforms or web forums, or they may have

provided their addresses in documents included in the legal

discovery process. Additionally, because of the increased know your

customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) regulations imposed

in certain jurisdictions, users are more frequently required to

provide their identities to gain access to the services offered by

centralized crypto institutions, such as crypto exchanges. While

these entities are typically reluctant to share information about

their users, sound analysis prepared by an experienced investigator

combined with a court order or subpoena can be leveraged to obtain

relevant account information for target individuals or entities

using their platform.

Finally, identification of individuals or entities can be

achieved through the analysis of blockchain activity to link

blockchain addresses and transactions to addresses previously

identified through other means throughout the investigation. This

concept is similar to the Mosaic Theory in finance, whereby

cryptocurrency investigators can gather and analyze data from a

wide variety of sources to develop a probabilistic understanding of

address ownership that is not available from one single source of

data. Once investigators have identified the addresses and wallets

of individuals related to the investigation, they can subsequently

work forward or backward to trace assets associated with that

individual and identify additional addresses of interest.

Blockchain Data Sources

Leveraging the public nature of blockchain transactions is of

the upmost importance to a successful crypto asset investigation.

Investigators will need to extract and analyze public blockchain

data to identify transactions that occurred on-chain. Subsequently,

this data may need to be supplemented with account data from

centralized exchanges or over-the-counter (OTC) trading desks,

which can be obtained through subpoenas or legal discovery as noted

above.

A publicly available, widely accessible (and free) source of

blockchain data is block explorers, which are web-based blockchain

data interfaces that provide a relatively straightforward means for

users to explore and search for certain data recorded on a

blockchain, including transactions, addresses, and smart contract

code. Prominent blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, have

extremely reliable and well tested block explorers (i.e.,

Blockchain.com for Bitcoin, Etherscan for Ethereum).

Conversely, smaller or less used blockchains may have limited

block explorers that lack proper technical support, offer poor user

interfaces, or may have no usable public block explorer at all, and

the reduced reliability, usability, and completeness of those tools

may complicate blockchain forensics and investigative procedures.

In some cases, the block explorers may be built by the same

individuals who designed the blockchain, and these insiders may

have an incentive to sensor or falsify blockchain activity that

appears on the block explorer interface available to users.

When investigating transactions, addresses, or protocols built

on blockchains without reliable block explorers, it is critical

that investigators conduct testing on the reasonableness and

completeness of the data sources being used. Inconsistencies or

discrepancies in data presented on the block explorer or between a

block explorer and another blockchain analytics tool may be

indicative of an unreliable block explorer. When there is any

concern regarding the quality or completeness of a block explorer,

investigators should either run their own blockchain node to access

the full history of that blockchain or consider relying on other

blockchain data providers who are running their own node.

Finally, investigators will need to obtain and understand data

from centralized exchanges, OTC desks, or other entities who

execute transactions involving crypto assets

off-chain. These entities provide trading

and other services for their users on their own systems and not on

the public blockchain (i.e., off chain). As a result,

investigators can trace and analyze crypto asset transactions using

public sources until it is sent to a centralized, off-chain entity.

In order to continue the tracing of crypto assets, investigators

will need internal account and transactional records from these

entities. As noted above, it is not a guarantee that you will be

given access to records from these entities depending on their

jurisdiction and willingness to cooperate with the investigation.

Additionally, even when requested data is provided, the data

points, formatting, and account structure in the documentation

received can vary widely.

Crypto Asset Tracing

The methodologies and assumptions used to trace assets through

and across blockchains can result in substantial differences in the

conclusions reached by investigators and blockchain forensics

practitioners. While parallels exist between traditional financial

instruments and crypto assets when it comes to tracing

methodologies, there are several critical nuances that are unique

to cryptocurrencies, including the underlying model used by each

blockchain to process and record transactions, the bifurcation

between wallets and addresses for tracing purposes, and the novel

types of transactions an investigator may come across. Moreover,

the tracing itself will be dependent on the quality of data sources

available and wallet identification procedures outlined above.

UTXO vs Account Based Blockchain Models

There are two primary models for recording the state of a

blockchain and recording transactions—the unspent transaction

output (UTXO ) model, which is used by

Bitcoin, and the account based model, which is used by

Ethereum.

Under the UTXO model, each input to a transaction

(i.e., the source of funding for a transaction) was

previously an output from another transaction (i.e., the

destination of funds in a transaction). The corresponding output is

a UTXO, until it is subsequently used to fund a new transaction,

where it becomes an input to a new transaction and the UTXO becomes

a spent transaction output. An additional consideration with

UTXO-based blockchains is that the blockchain tracks the ownership

of individual UTXO’s to various addresses, rather than

maintaining a record of the total balance of each crypto asset held

by that address. As such, wallet software and blockchain analytics

tools for UTXO-based blockchains take the sum of the UTXOs

associated with an address to determine the balance of each crypto

asset held for that address.

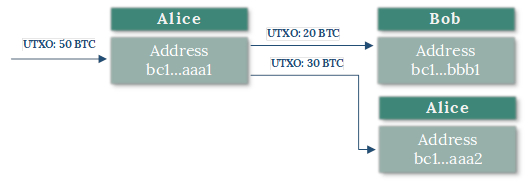

For example, if Alice wants to send 20 Bitcoin to Bob, and she

has a UTXO of 50 Bitcoin, she will send 20 Bitcoin to an address

provided by Bob, and the remaining 30 Bitcoin will be sent to an

address that she owns (this is referred to as a “change”

address). Both the 20 Bitcoin sent to Bob and the 30 Bitcoin sent

to Alice’s address are now new UTXOs, and the original 50

Bitcoin UTXO has become a spent transaction output. After this

transaction, Alice now holds a new UTXO of 30 Bitcoin and Bob holds

a new UTXO of 20 Bitcoin (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Diagram of UTXOs and Change

Addresses

Alternatively, an account based blockchain model is typically

considered more similar to bank accounts in the traditional

financial system. The blockchain maintains a record of the balance

of assets for each account (or address) and a transaction involves

debiting one address and crediting another. There is not a direct

technological link between a transaction’s inputs and a prior

transaction’s outputs.

The distinction between these two methodologies is critical to

understand for an investigator because of the impact on which

tracing methodologies are used and whether to group assets by

wallets or by addresses (which is discussed in more detail below).

Because of the explicit link between the inputs and outputs of a

transaction under the UTXO model, a practitioner could trace the

assets in one UTXO backward to its original source through several

hundred transactions based entirely on which UTXOs were used in

those previous transactions and without any consideration for the

other UTXOs owned by an address.

While the direct tracing of UTXOs can be highly useful for

investigators and a convincing piece of evidence, it does raise a

theoretical question about the fungibility of assets built on a

UTXO model. This issue is further complicated by the technical

experience of the owner of the address. Some highly advanced market

participants may intentionally structure UTXOs to fit or obfuscate

a specific pattern, whereas a less proficient user may allow wallet

software to select which UTXOs to be used as inputs in a new

transaction. Ultimately, the professional judgement of the

investigator and a comprehensive understanding of the supporting

facts of the investigation is critical to determining whether a

last in, first out (LIFO), first in, first out (FIFO),

Lowest-Intermediate Balance, or UTXO methodology should be

applied.

Wallet vs Address Level Tracing

A cryptocurrency wallet can generally be thought of as a

collection of different cryptocurrency addresses with common

ownership. When sending or receiving a transaction on a blockchain,

funds will move directly to or from an individual address (or

addresses), not from a wallet. Because of this distinction,

investigators will often need to determine whether they are tracing

assets from an entire cryptocurrency wallet or from individual

addresses for tracing analyses.

Address re-use is a critical consideration in determining

whether to use a wallet level or address level tracing approach.

Addresses in an account-based model are commonly re-used by the

address owner, like how a traditional bank account is used.

However, some market participants in a UTXO based blockchain

implement and encourage the use of single-use addresses to enhance

privacy and security, among other reasons, and in many cases UTXO

wallet software will automatically generate new addresses for each

new transaction in the wallet. This means that each address is only

used to send and/or receive assets once (see Figure

3).

As noted above, some technically proficient users may

intentionally determine which UTXO to use as a transaction input,

as well as what address should receive the new UTXO. Conversely,

other users may rely on their wallet software to make these

determinations for them. However, in just looking at blockchain

data, it may not always be clear that an address is part of a

wallet with other addresses. The data available, the sophistication

of the user, the transaction activity in relevant addresses and

wallets, and a proper understanding of the blockchain model being

used must all be considered by the investigator in deciding whether

to trace assets by wallet or address.

Other Considerations

There are several additional issues that investigators should be

aware of during their review, including novel transaction types and

associated regulatory risks, different consensus mechanisms, and

the additional functionality of crypto assets built on top of smart

contracts. These considerations are vast and highly complex, and a

detailed discussion of each of these topics would be impossible to

address in this article alone. However, investigators need to be

aware of these nuances to properly understand and evaluate the

relevant facts, and as a result we will briefly address some key

considerations surrounding these issues below.

Many blockchains enable the use of smart

contracts, which is computer code that can be stored at

its own address on the blockchain. Smart contracts are

self-executing and follow a defined protocol the same way every

time depending on the contract inputs. Smart contracts allow for

additional functionality for crypto assets beyond just sending and

receiving assets and are the building blocks of many decentralized

finance (DeFi) applications.

One such novel functionality is the use of crypto asset

tumblers, or mixers, which are a privacy solution

used to substantially reduce the ability of investigators to trace

assets. Users can send crypto assets to a mixer service, which

pools large amounts of crypto assets together, commingles them, and

subsequently distributes the funds to destination addresses. This

commingling of funds obscures the trail of crypto assets and can

make subsequent tracing difficult. The use of mixers is a highly

contested regulatory issue and has raised money-laundering concerns

by regulators and enforcement agencies.

Decentralized savings and lending protocols are another

blockchain protocol functionality that is built on top of smart

contracts. These protocols allow users to deposit crypto assets

into a pool of funds in order to earn interest, in the form of

other crypto assets, which is generated by users borrowing from the

pool, similar to a bank savings account. Users will often receive a

“voucher” token in exchange for their crypto asset

deposit that represents their right to and ownership of a

percentage of assets in the savings pool. This voucher can be

bought and sold like the underlying crypto asset deposited in the

pool or it can be exchanged later to redeem the original deposit

plus interest.

Finally, there are several different consensus mechanisms that

blockchains use to achieve a decentralized consensus among market

participants to confirm and validate the transactions executed by

users on the blockchain. These consensus mechanisms are a

fundamental part of the underlying blockchain protocol and are

critical to its operation as there is no central authority that can

act as a source of truth for the ledger and the validity of

transactions. These consensus mechanisms can be thought of as a

decentralized solution to a lack of a traditional centralized

clearinghouse. These mechanisms are highly complex and could be the

subject of their own whitepaper, however, the two most common

consensus mechanisms are Proof-of-Work (PoW),

which is used by Bitcoin, and Proof of Stake

(PoS), which is used by Ethereum.

Proof-of-Work relies on blockchain miners to

solve a cryptographic hashing puzzle with specialized computing

equipment resulting in a solution that fits the parameters of the

Bitcoin protocol’s difficulty adjustment. In the case of the

Bitcoin blockchain, the miner who correctly solves the puzzle, is

awarded with the right to “mine” the next block of

transactions and is compensated with the transaction fees of

transactions included in the block as well as the block reward,

which is cut in half roughly every four years, or every 210,000

blocks, and was recently reduced from 6.25 Bitcoin to 3.125

Bitcoin.

2 The block reward is also how the issuance schedule

of new crypto assets is determined and the only way in which new

crypto assets are created.

Proof-of-Stake relies on the staking of crypto

assets by market participants to achieve consensus. Stakers will

effectively lock an underlying crypto asset, which must be the

native token of the blockchain, as collateral into a staking smart

contract for a pre-determined amount of time. The protocol then

uses a combination of random selection and characteristics of the

assets staked to determine which user will “forge” the

next transaction. Similar to Proof-of-Work, the validator (or

staker) that forges the next block will receive a block reward of

newly issued assets and transaction fees of the transactions

included in the block.

Crypto assets and the blockchains that facilitate their use are

highly complex, and related investigations involve a wide variety

of new considerations for investigators that are unique and that

may differ or overlap with the tracing of and investigations into

traditional financial assets. This article should provide a general

foundation, but if you have any questions or would like to discuss

the nuances that can impact crypto asset investigations further,

please reach out to the experienced professionals at Ankura for

further information.

Footnotes

1 https://www.sec.gov/spotlight/cybersecurity-enforcement-actions

2 The block reward was cut in half from 6.25 Bitcoin to

3.125 Bitcoin during the most recent halving, which occurred on

April 19, 2024, at block height 840,000.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.