Jobs

East and Gulf coast dockworkers strike, sparking fears of inflation and shortages again

Consumers can face higher prices, less supply with port worker strike

If about 45,000 union works from 36 ports from Boston to Houston walk off the job in strike, consumers will feel the impact.

Dockworkers at ports from Maine to Texas are officially on strike after the clock struck midnight with no new labor deal in hand.

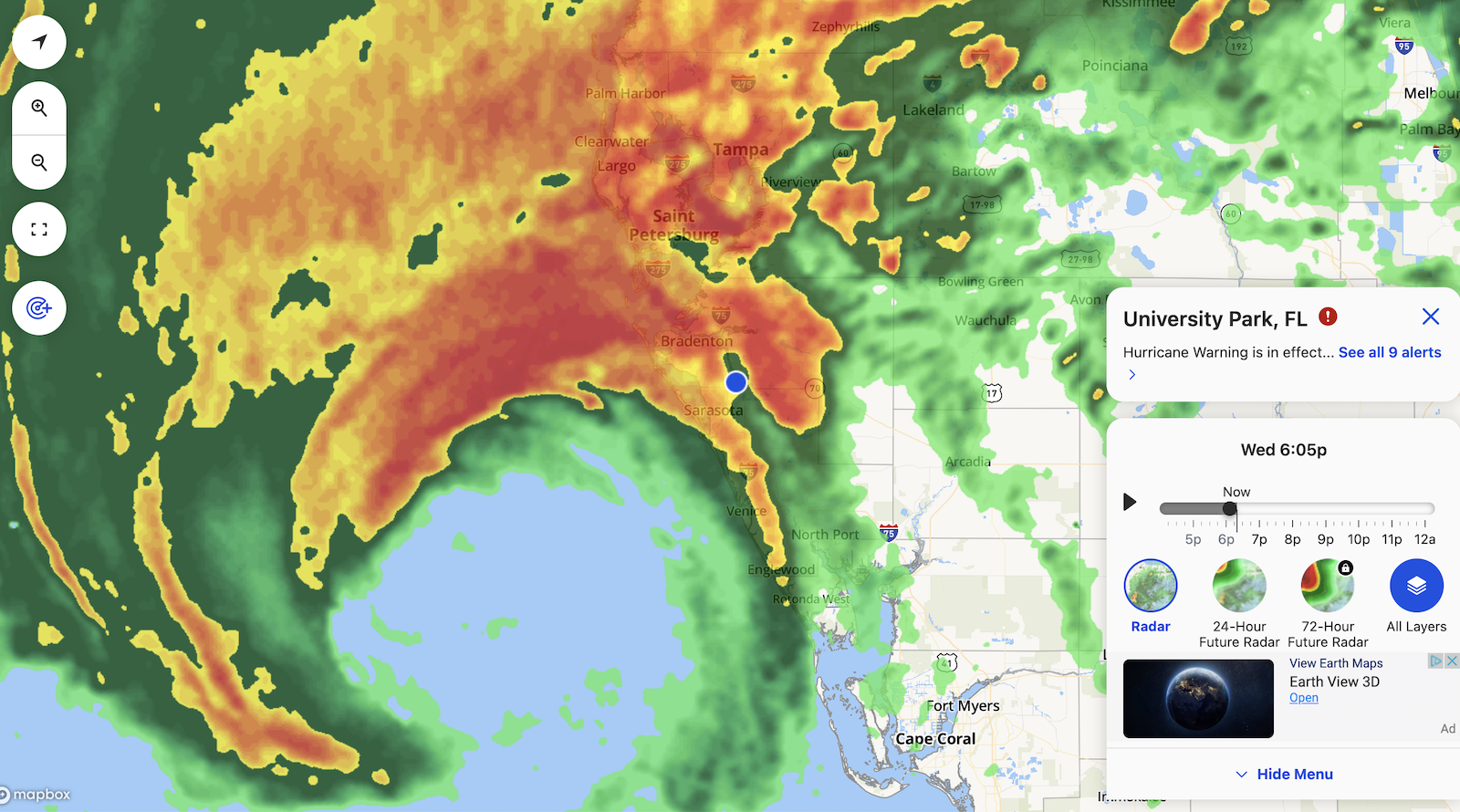

Thirty-six East and Gulf coast ports shut down as 45,000 union workers walked off the job after labor negotiations stalled between the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) and the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX). The strike only exacerbates some temporary port closures in places like Florida, the Carolinas and Georgia in the wake of Hurricane Helene.

The ILA strike is the first at these ports since 1977 and has the potential to cost the economy up to $5 billion a day, upend holiday shopping for millions of Americans and dictate whether many small- and medium-sized businesses and farmers turn a profit or lose money this year, experts said.

“Every idle day that a ship does not get into the port costs money and sometimes a lot of money…that ultimately gets passed onto consumers,” said Stamatis Tsantanis, chairman and chief executive of shipper Seanergy Maritime and United Maritime, in a statement.

Length matters

Now that the strike is on, experts will turn their focus to how long the strike may last. Each day of the strike could cost the economy up to $5 billion a day as imports and exports are blocked, some economists estimated.

“It’s not just about the shutdown but also, about the recovery period and how long it takes to get things up back and running,” said Jonathan Gold, vice president of supply chain and customs policy at the Nation Retail Federation.

For each day of the strike, it takes about three to five days to clear the backlog and resume normal operations, he said. “The longer it goes, the more it gets compounded,” he said.

A port strike in 2002 went for 11 days before the Bush administration invoked the Taft-Hartley Act to force the ports to reopen. The Act allows the federal government to seek a court injunction against a strike to allow both parties to continue negotiations during an 80-day cooling off period. It took six months to recover from those 11 days, Gold said.

Despite many industry groups calling for intervention, the Biden administration said it doesn’t intend to invoke Taft-Hartley. Instead, it encouraged continued negotiations and said in a statement that it would carefully monitor supply chain disruptions and “respond swiftly to help minimize potential disruptions in the event of a prolonged strike by engaging extensively with the ports, state and local officials, industry, labor, ocean carriers, rail and trucking companies.”

What to expect: A port strike could cost the economy $5 billion per day, here’s what it could mean for you

What’s affected by the strike?

Imports: With about half of U.S. ocean imports passing through the East and Gulf coast ports, a wide range of products are affected, including produce, cars, auto and machinery parts, clothing, pharmaceuticals, wine and spirits, holiday goods like toys, and seafood, experts said.

“Any strike that lasts more than one week could cause goods shortages for the holidays,” said Eric Clark, portfolio manager of the Rational Dynamic Brands Fund. “Retailers are running lean currently so inventory would get drawn down, and prices of shipping, and goods prices would go vertical for a period of time. We could get the kind of inflation for 6 months similar to or worse than peak inflation levels a year ago.”

Small and medium-sized businesses could suffer most, some said.

“Large businesses with dedicated procurement departments and considerable access to capital have been preparing for this strike for some time and many have ordered excess materials which they were able to finance with lower-cost debt,” said Ben Johnston, chief operating officer at small business lender Kapitus.

“Small businesses, however, are less likely to have been able to order early and in bulk and are less likely to obtain the capital required to order larger quantities of supplies in advance,” he said.

Exports: Businesses that sell products to international markets would suffer, experts said. For example, agricultural exporters of soybeans and poultry won’t be able to send their goods overseas and could end up losing market share, or worse, lose money because their goods are perishable, they said.

Jobs: Companies keeping lean inventories to keep costs low might have to shut down assembly lines amid a prolonged strike, for example, Gold said. This would come at a time when the job market is already cooling.

Medora Lee is a money, markets, and personal finance reporter at USA TODAY. You can reach her at mjlee@usatoday.com and subscribe to our free Daily Money newsletter for personal finance tips and business news every Monday through Friday morning.