Bussiness

Mason-Dixon Line: How a Cotswold astronomer helped define US politics

BBC

BBCAs US voters head to the polls today, it is clear that there is a stark divide between supporters of the two leading candidates.

Political division across the pond is nothing new, with conflicts spanning back hundreds of years.

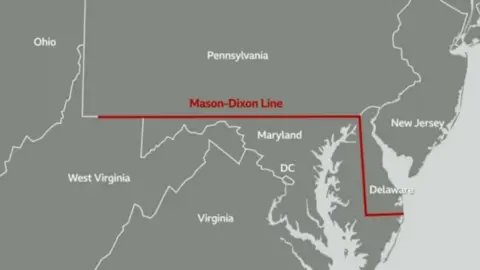

For decades, this separation has been symbolised in political circles by the Mason-Dixon Line – a historic cultural boundary between the north and south of the United States.

But much less known is the story of the eponymous astronomer Charles Mason, and his roots in rural Gloucestershire.

In the 18th Century, Mr Mason and fellow English astronomer Jeremiah Dixon, from County Durham, were commissioned to chart a boundary line intended to settle a long-running dispute between the Penn family – proprietors of Pennsylvania – and the Calverts, proprietors of Maryland.

Using instruments to help them track the path of the stars, they spent five years after their arrival in 1763 plotting the line with stone markers brought from England – some of which still stand today.

They couldn’t have known it then, but a century later their line would symbolise something far more insidious than land ownership.

In the pre-Civil War period it became part of the dividing line between slave states south of it and free states north of it, and the names Mason Dixon are still invoked today as a symbol of the United States’ deep political divides.

There is evidence that Mr Mason was friends with one of the United States’ most famous political figures and founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin.

Even in death he found himself in the company of US political giants, having been buried in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia – the final resting place of Mr Franklin, as well as four other signatories of the Declaration of Independence.

He even has a crater on the moon named after him.

But how did a boy, born into the humblest of Gloucestershire families, find himself in such high places?

His enduring legacy would have seemed incredibly unlikely back in 1728, when Mr Mason was born the son of a miller and baker in Oakridge, a village near Stroud.

Speaking to the BBC inside St Kenelm’s Church in nearby Sapperton, heritage learning officer Marie Sellars from the Churches Conservation Trust described Mr Mason’s deep links with the building and area.

“His parents were married here, he was baptised here and he lived locally,” she said.

“Not much is known about his early life but we do think that he probably ended up going to grammar school in Tetbury and he had a gift for mathematics.”

It was this gift, Ms Sellars explained, that may have led to him getting a job with the Astronomer Royal at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

Nathaniel Bliss, the holder of the post at the time, hailed from the Cotswold village of Bisley and, Ms Sellars said “might have been passed on information” about a young Mr Mason’s talent for maths.

‘So extraordinary’

“To actually go to grammar school at that time would have been phenomenal for someone from such a humble background, at a time when school wasn’t an option for lots of people – especially grammar school,” Ms Sellars said.

Having made a name for themselves mapping the transit of Venus, Mr Mason and Mr Dixon were asked by the Royal Society to travel to the US to map the line – arriving in the early 1760s with a crew of fewer than 10 men.

“Some of the instruments they brought with them were so extraordinary,” Ms Sellars said. “There’s a story about their telescope that had to be transported on the back of mattress because it was so big and so delicate.”

Guided by the stars, they planted a stone every mile – each one with the letter P for Pennsylvania and a M for Maryland on each side, and at every five miles planted a marker with the heraldry of the two families then in charge of the states.

“It was an amazing feat because it was something that no one had done before – it actually proved to be quite accurate,” Ms Sellars said.

After completing the project with Mr Dixon, Mr Mason returned to the area he had grown up in – marrying his second wife at St Kenelm’s and having four more children.

The grave of his first wife, Rebekah Mason, can still be found in the churchyard today.

He decided to return to America in 1786 with his wife and eight children.

However, during the voyage across the Atlantic he was taken ill, and he died less than a month after arriving back in Philadelphia in October 1786.

While Mr Mason may not be a widely-known figure himself, Ms Sellars said that people still visited St Kenelm’s to seek a connection with his history.

“These buildings contain lots of people’s stories and histories, but to have somebody that’s not just locally known but nationally and internationally known is phenomenal,” she said.