Tech

The U.S. And China Are Making Two Tech Worlds, Together

Xi Jinping and other leaders of the Communist Party of China and the state, together with the two … [+]

Recent developments highlight the United States’ and China’s shared interest in bifurcating technological development – a sector that has long benefited from globalization.

Leaders in both Beijing and Washington have reached two conclusions. The first is straightforward: Innovation is the best and only key to economic growth and geopolitical leadership. The second: To win the sci-tech advantage, each country must take robust public and private sector measures to compete with (and separate from) the other.

These dynamics were at play before the rise of artificial intelligence. AI’s now-ubiquitous relevance has added another layer to the tech war. The confluence of the China “threat” and the “risks and opportunities” presented by AI has created an opening for American tech companies to get on their government’s good side — and stifle the AI capabilities of the country home to their major competitors in the process.

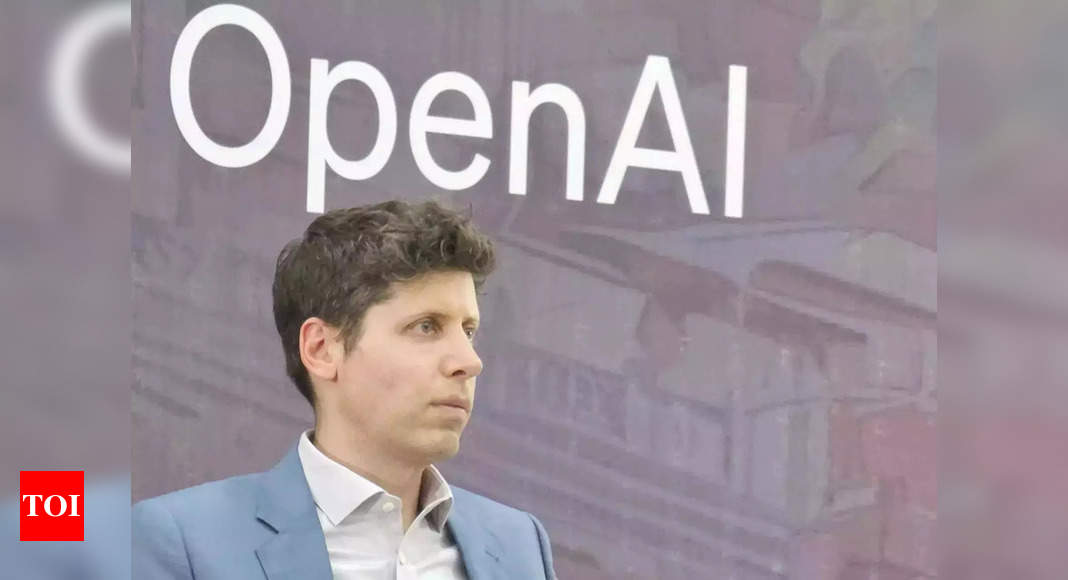

For example, Chinese media reported OpenAI will take additional measures to restrict API traffic from countries where its services are not supported (such as China). Domestic Chinese competitors like Zhipu AI are looking to fill the gap, but another made-in-America restriction stands in their way: chip controls. That’s because U.S. semiconductor export controls aimed at China limit the country’s access to the computing power a domestic company would need to fully replace OpenAI.

More recent U.S. government moves have further solidified the strategic direction of creating two separate and, the idea is, decidedly not equal tech landscapes: one in America and the other one in China.

For example, on June 21, the Treasury Department released proposed rules to implement last year’s Executive Order restricting Americans’ tech-related investments into China. According to Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Investment Security Paul Rosen, “President Biden and Secretary Yellen are committed to taking clear and targeted measures to prevent the advancement of key technologies like artificial intelligence by countries of concern from threatening U.S. national security.”

Elaborating on AI, the proposed rules put forth “a prohibition on covered transactions related to the development of any AI system designed to be exclusively used for, or intended to be used for, certain end uses.” While this circuitous language hints at military uses, its vagueness could allow for restrictions aimed at more benign “end uses” in practice.

While the United States expedites the great tech divide, leaders in Beijing are in turn expediting their plans to domesticate innovation – which predate America’s punitive measures aimed at China’s tech sector, but have been sped up by them. As Xi Jinping put it at last week’s National Science and Technology Awards Conference, “The scientific and technological revolution and the great power game are intertwined.”

His diagnosis of how China should compete in this context is both comprehensive and short on policy details. He called for integrating science, technology, and industry and investing resources in “key areas and weak links.” R&D, according to Xi, should be taken on in direct response to bottlenecks China faces in areas such as semiconductors “to ensure the autonomy, security, and controllability” of important supply chains.

He advocated for companies to work with universities and research institutions (the idea is to ensure innovative breakthroughs have commercial viability and, conversely, that marketable products manifest technological breakthroughs).

Xi also highlighted the significance of cultivating talented personnel – the resource China has high hopes for and arguably the most control over. He called for creating a talent job market and ecosystem that is internationally competitive and perhaps granting sci-tech researchers the trust and freedom they need to succeed.

Xi’s speech only reiterated the across-the-board approach China is taking to advance innovation – both for its own economic success and to compete with the United States. Washington’s more recent moves toward integrating government and industry in recent years has been more of a divergence in a U.S. policy context. Its continuation is also contingent on the upcoming presidential election.

Yet it makes sense. Whatever one thinks of the decided-upon objective, (beating China in all areas at all costs) achieving it will take public-private coordination. For now, it looks like the U.S. tech and policy communities are sufficiently aligned to take on, and possibly achieve, their common goals.

But it wouldn’t take much for that alliance of convenience to dissipate. The unity China enjoys between party, state, and industry, while not perfect, is far more central to the leadership’s overall ability to remain in power. Coordination is therefore more prioritized and, possibly, more likely to yield long-term results in the two tech world future both countries’ leaders seem primed to deliver.