World

The world needs a US president who respects evidence

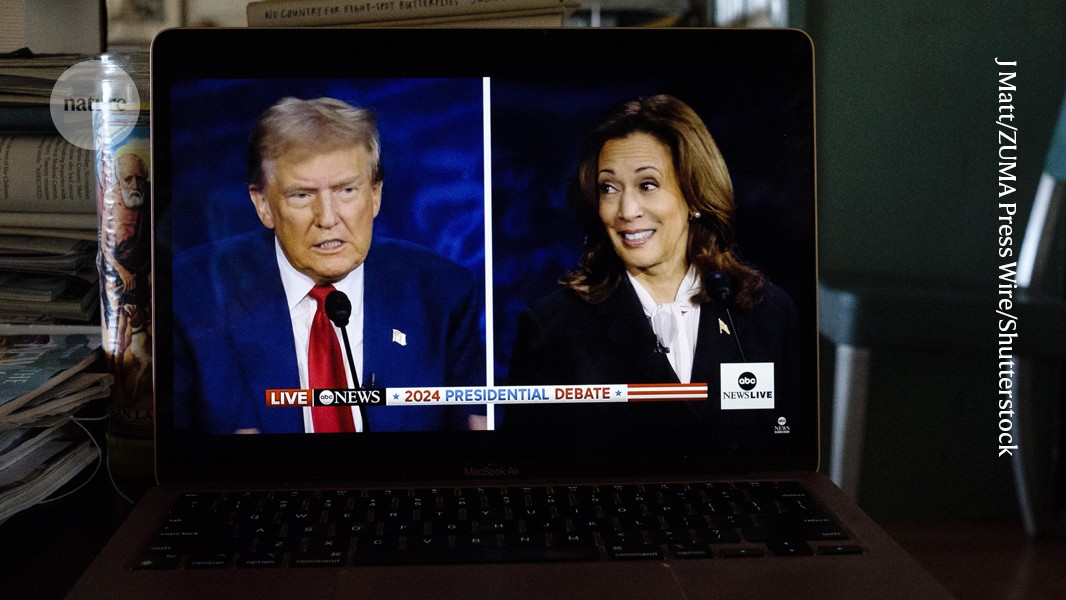

Kamala Harris and Donald Trump at their first (and only) televised debate, on 10 September.Credit: J Matt/ZUMA Press Wire/Shutterstock

Next week, US voters will go to the polls to elect a new president, along with members of the House of Representatives and the Senate. This election will take place at a time of extreme uncertainty, both for the United States and for the world. The two candidates, Democrat Kamala Harris and Republican Donald Trump, represent vastly different views of the challenges and opportunities that the country faces, and the role of the United States on the international stage.

The US is the world’s science superpower — but for how long?

Like all elections, the 5 November vote is about much more than science. However, the fate of scientific research, evidence-based lawmaking and the government’s receptiveness to independent science-policy advice will be key determinants of the country’s future course and long-term well-being. And, as we reported in a News Feature on 23 October (Nature 634, 770–774; 2024), US science could be at an inflection point: the election and a range of domestic and global forces could challenge the primacy that the country has held since the Second World War.

A priority for both the winning presidential candidate and the new members of Congress must be ensuring that US science continues to thrive. This is essential if the world is to solve shared challenges, such as the climate crisis, inequality and societal divisions — and that means retaining the openness and collaborative spirit that have characterized US science for much of the past 75 years. US scientists work with peers around the world, which has helped to position the country at the centre of fundamental, applied and translational research, while creating bonds of friendship and collegiality between US researchers and their international collaborators. These bonds are needed now more than ever.

Power and responsibility

The United States needs leaders who fully understand the responsibilities that come with power and, moreover, are wholeheartedly committed to respecting facts or the consensus of evidence while governing.

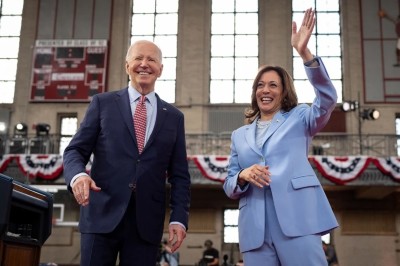

Harris, the vice-president under President Joe Biden, is a former US senator; before that, she was a public prosecutor and attorney general in California. In her previous and current roles, she has broadly sought to advance policies that are in line with the scientific consensus and with the objective of keeping people safe and protecting public health and the environment.

What Kamala Harris’s historic bid for the US presidency means for science

The Biden–Harris administration’s signature achievement is the plan to invest more than US$1 trillion in climate and clean-energy technologies over a decade — albeit while overseeing record levels of production of oil and natural gas in the short term. A landmark piece of legislation passed by Congress in 2022, called The Inflation Reduction Act, is a historic investment that seeks to modernize US manufacturing and create jobs in the clean-technology industry. At the same time, the administration has sought to craft and implement plans to insulate regulatory agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), from political interference.

Harris said on 22 October that her administration will not be a continuation of the Biden presidency. She has said she wants to build an “opportunity economy”. Precisely what that means is yet to be defined — a science- and evidence-based approach needs to be at its core.

That record is in stark contrast to what happened during Trump’s presidency, from 2017 to 2021. As president, Trump not only repeatedly ignored research-informed knowledge, but also undermined national and global science and public-health agencies. He has denied climate science, lied about the federal government’s response to hurricane forecasts and asked scientists to investigate whether disinfectants could be used to treat people with COVID-19.

He pulled the United States out of the World Health Organization in the middle of a once-in-a-century pandemic. He withdrew the country from both the Paris climate agreement and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (also called the Iran nuclear deal) — both of which the United States had helped to craft. He instilled fear at the EPA, including by rolling back climate policies and making it harder for its research workforce to be able to function independently of politicians, as many EPA scientists told Nature at the time.

Mounting risks

If anything, Trump’s speech has coarsened. In the past few weeks alone, he has falsely claimed that millions of migrants are “pouring into our country from prisons, jails, from mental institutions and insane asylums” and eating people’s pets, and that members of the Democratic Party support the execution of babies after birth.

Effort to ‘Trump-proof’ US science grows, but will it succeed?

The risks of a second Trump presidency continue to mount. It wouldn’t be easy for a new administration to reverse the investments pledged by the Inflation Reduction Act, but Trump has promised to try. He has said he will ramp up fossil-fuel production and promised to reclassify the positions of tens of thousands of federal employees, including scientists and senior officials in the executive branch of government. That is an alarming development that would require reversing the rule that the Biden administration has crafted to prevent such action. It would undermine a basic premise of modern governance the world over: that scientific and technical specialists working in government are recruited for their expertise, not on the basis of their loyalty to the president or a political party, which is what Trump wants to do.

Political leaders, irrespective of party membership or ideology, generally agree on the need for a society that creates jobs, promotes better health and advances science. But solutions for the world’s mounting problems can come only from a shared, accurate understanding of reality.

A lack of regard for the law and evidence fosters mistrust of scientists and institutions of state. That, in turn, weakens the foundations of democracy, both in the United States and around the world. A second Trump presidency would have an even more destabilizing effect globally, giving the green light to yet more leaders like him.